Lời nói đầu:Analysis of the decline of the 1945–2025 liberal world order—from Fukuyama’s “End of History” thesis to Xi Jinping’s Taiwan reunification declaration and Trump’s 2026 Venezuela oil deal—paving the way for multipolar realism.

In 2026, profound shifts in global geopolitics are underway as bold statements on Taiwan from China and U.S. energy policy in Venezuela expose the weakening of the post-World War II liberal world order. In its place, a multipolar world grounded in realism is gradually emerging.

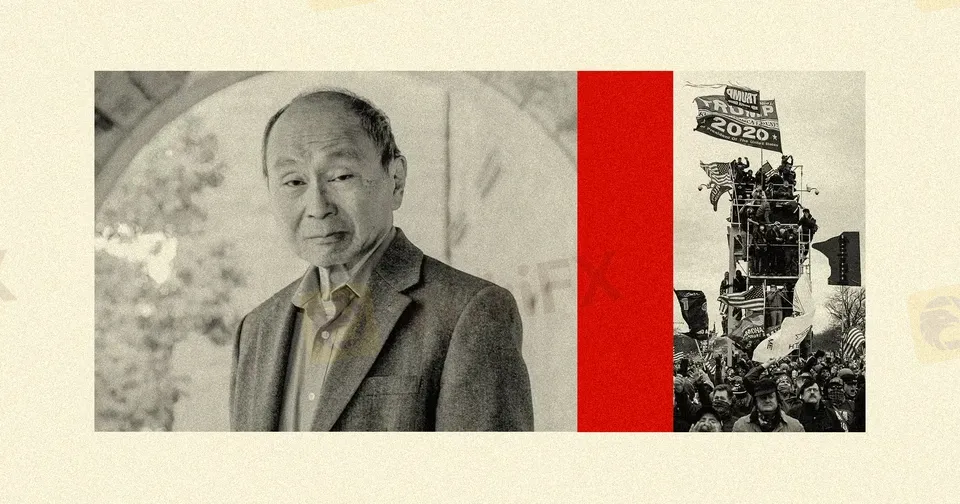

Three decades ago, in 1989, American political scientist Francis Fukuyama sparked intense debate with his essay “The End of History?”. He argued that the collapse of communism and the triumph of Western liberal democracy marked the endpoint of humanitys ideological evolution.

According to Fukuyama, the 20th century saw the developed world plunge into ideological violence - from absolutism to Bolshevism, fascism, and updated Marxism that threatened nuclear apocalypse. Yet by centurys end, Western economic and political liberalism appeared to have achieved an unequivocal victory. No viable systematic alternatives remained.

Major communist powers like China and the Soviet Union were initiating significant reforms. Consumerist Western culture was spreading inexorably - from peasant markets and color televisions in China, to cooperative restaurants in Moscow, Beethoven in Japanese department stores, and rock music in Prague, Rangoon, and Tehran.

Fukuyama concluded: “What we may be witnessing is not just the end of the Cold War… but the end of history as such: that is, the end point of mankinds ideological evolution and the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government.”

In the context of 1989, such optimism was understandable. The United States led a global liberal order underpinned by institutions like the United Nations, WTO, and NATO. International law, though imperfect, served as a guiding framework for cooperation and peace. Liberalism promised a world where democracies do not war with one another - per Kants democratic peace theory - and international institutions could foster lasting cooperation.

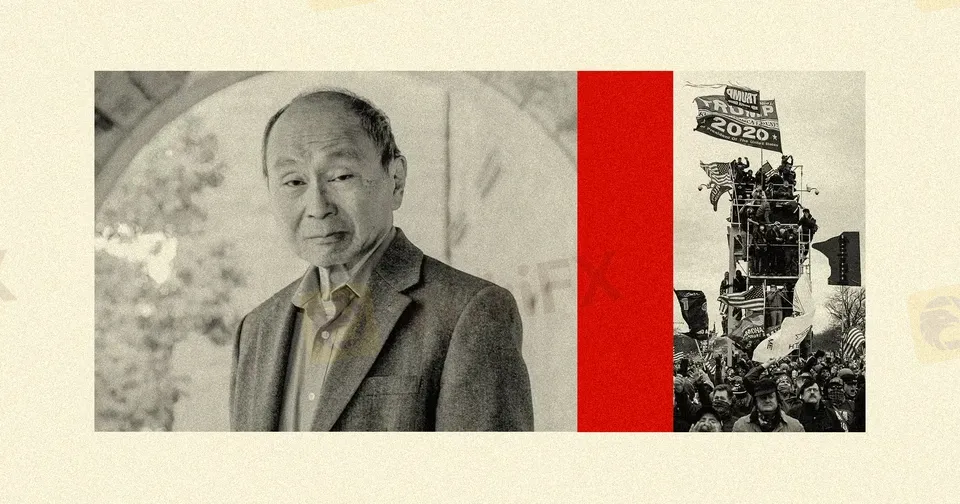

By 2026, however, that vision has changed dramatically. The post-1945 Liberal World Order appears to be reaching its limit—not through sudden revolution, but through accumulated developments: the rise of new powers and the increasingly open pursuit of national interests without the veneer of democratic ideals or international law.

A clear example comes from China. In his 2026 New Years address, President Xi Jinping declared: “We Chinese on both sides of the Taiwan Strait share blood ties and kinship. National reunification - a trend of the times - is unstoppable!”

While the substance is not new, the assertive tone and timing signal Beijing‘s growing disregard for international opinion. China has long viewed Taiwan as an inseparable territory lost during last century’s civil war. Yet publicly emphasizing “unstoppable” reunification amid escalating cross-strait tensions sends a powerful message.

Many analysts believe that if unification cannot be achieved through economic or political pressure, Beijing may consider military options in the near future. While a full-scale invasion remains high-risk, “gray zone” tactics, large-scale exercises or economic blockades, have become routine tools. This shift reflects Chinas growing confidence in its national power and exposes the limits of international law when facing a military power capable of challenging the status quo.

On the other side of the globe, the U.S. administration under President Donald Trump is adopting a similarly pragmatic approach, less reliant on traditional liberal rhetoric. Washington recently announced the first Venezuelan oil sale worth $500 million under a new agreement. This marks the initial step in releasing tens of millions of previously blocked barrels, with a total value potentially reaching billions.

President Trump stated that major U.S. oil companies will invest hundreds of billions to rebuild Venezuelas severely degraded infrastructure - damaged by mismanagement and corruption, causing production to fall from 3.5 million barrels per day at the turn of the century to roughly 800,000 today.

Venezuela holds the worlds largest proven oil reserves, exceeding 300 billion barrels. The deal not only delivers direct economic benefits but also reinforces U.S. regional influence. White House statements frame the agreement as protecting the Western Hemisphere from drug crime and foreign adversaries. This approach contrasts sharply with early-2000s military campaigns justified as “bringing democracy” to Iraq or Afghanistan. Today, resource interests and regional hegemony are stated plainly, without ideological packaging.

These developments are not coincidental. They reflect a broader transition from liberal institutionalism to multipolar realism. Realism views the world as anarchic, where states are unitary rational actors competing to maximize power - the only variable that truly matters. International institutions like the UN, from a realist perspective, do little to constrain states and often serve merely as vehicles for great-power interests.

Liberalism, by contrast, holds that a states internal characteristics shape its international behavior, and institutions can promote sustained cooperation. Democratic peace theory posits that democracies do not fight each other, while liberal institutionalism expects global organizations to deliver peace.

The reality of 2026 shows realism gaining ground. Analysts from independent think tanks describe the world as moving toward “multipolar” or “multi-domain” arrangements, where U.S. unipolar hegemony has faded. The rise of China, India, and blocs like BRICS is blurring the post-Cold War order.

Experts at Project Syndicate and Chatham House warn that the West is unprepared for this multipolar era, where global cooperation will be more selective and interest-based rather than rooted in universal values. In Asia, Taiwan tensions could reshape global supply chains. In Latin America, U.S. re-engagement in Venezuela reinforces the classic principle that “the Western Hemisphere belongs to us.”

This shift does not imply total chaos, but it demands a more pragmatic outlook. International law persists, yet its effectiveness depends on enforcement power. Major powers increasingly prioritize national interests - from resources to strategic security. For the international community, this may bring greater diplomatic honesty, but it also heightens conflict risks when red lines are tested.

Looking back from 1989 to 2026, the liberal world order has come full circle. Fukuyama once celebrated “the end of history.” Today, history seems to be returning to timeless rules: power, interest, and competition. The new era may be less idealistic, but it is more candid. A multipolar world is taking shape, and how great powers navigate it will determine whether the coming decades bring peace or conflict.